Players: Justin Atkins, Nick Wedig, and Sean Nittner

Players: Justin Atkins, Nick Wedig, and Sean Nittner

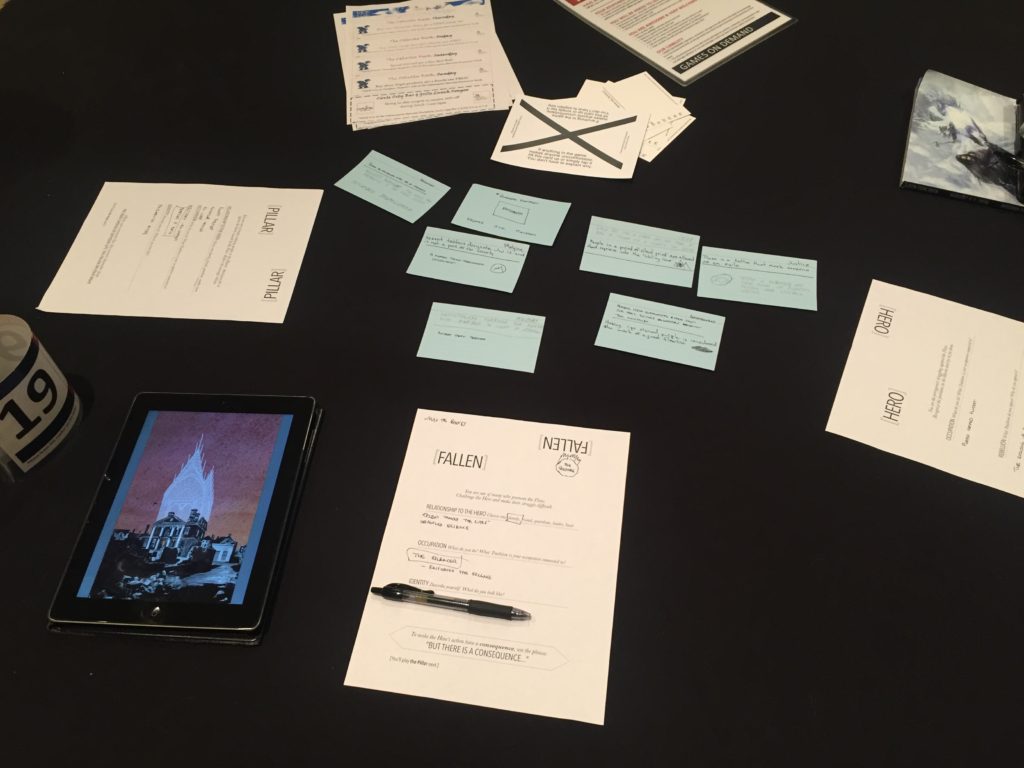

System: Downfall

The Pitch

Downfall is a tabletop role-playing game that explores the collapse of a society, a cataclysm brought about by a fatal Flaw at work within it. First you sit down and build your world, then you destroy it. You tell the story of a hero who tries to save their home. But in Downfall, the hero fails.

The game works in any kind of setting, from mythical fantasy to the real world to high-flying science fiction.

It’s made to tell a whole story in a single 2-4 hour session and doesn’t require preparation, dice, or a GM.

Why Downfall

I’ve been excited about Downfall for a while. I’m a big fan of games that are explicit about their end, and how you’ll get there. My Life With Master, A Penny for My Thoughts, Until We Sink, Fiasco, and the like. They all have some sort of structure that drives you to an end and in the case of Downfall, you even know the general shape of that ending…the hero fails and the society is destroyed. Having those creative constraints is awesome, and really makes me relish what we create within them.

I was also excited about a game that was GM-less, prep-less, and I thought could be played in two hours, though I turned out to be wrong all three times I ran it.

Finally I like tragic games like Montsegur 1244 and Polaris, where we know we’re playing to get the very most out of the little time we have. I’ve never played Grey Ranks (I think when my kids were younger, playing child soldiers hit a little to close to home for me) but I’d eagerly try if I had the opportunity now.

So, I had pretty high expectations of Downfall, and what I found (which will be spelled out over the three AP reports from Gen Con) was that it lived up to those expectations when we had a group prepared and ready to meet them. And less so when we didn’t.

The Fall of Guardian Mountain

The fatal flaw of Guardian Mountain was our nationalism. After a war for independence from a country that we strongly identified against, yet whose families were intertwined with ours, we drew very hard lines about what it meant to be a citizen, and how easily one could cross that line and be exiled or worse.

Given our current political climate this felt extremely poignant to me. We were talking about these people who lived on the top of a mythical mountain, but the same arguments they used to prop up their flaw as the highest virtue are arguments I see today during the presidential election. We weren’t going for political commentary, but it dipped in that direction just the same.

Traditions

Some of the richest part of our society was in it’s traditions, especially around silence, and how the ritual of silence was observed. Vows of silence were taken when people died, or when they were exiled. Breaking that silence early (or earlier than was expected) was a sign of disrespect. Maintaining it too long was a sign of being overly attached. It was so significant that the Fallen we made was named the Silencer, who had a perpetual vow of silence and shunned others into silence as well by their presence.

Tattoos were also a large part of the society, as they were very permanent. There was a tattoo that signified citizenship (a mountain top) and another that signified exile (the same mountain top upside down placed over the citizenship tattoo). The significance of this was that anyone could become a citizen, but once you were exiled, it was for life.

Hero, Pillar, and Fallen

Our Hero, Purple Lipped Flutist, was a veteran of the war who had put down the sword and taken up the flute, which stained their lips purple form the sap in the wood. She was quite literally the hero of the people, but her brother had been exiled for his beliefs and she knew the judgment was too severe and given because the code of silence, could not be questioned.

Our Fallen, the Silencer, was the Heroes uncle and wanted more than anything, to shame her into submission to his will. She was a powerful symbol but only if she could be controlled and he did so by turning those who she loved most against her.

The Pillar, Carries a Torch, was also a military commander in the war and now in charge of security always carried a torch such that a signal fire could be lit in the case of invasion [This was the sign of office for a guard]. He and the hero had once been very close during war time but now they were separated by duty. He of course, also “carried a torch” for her. Carries a Torch was pitted over and over again against the Hero, and simply wanted her to comply so that she would not cause trouble. He loved her and wanted her to be safe. He didn’t see what she saw.

Song of Rememberance

In our first scene, Purple Lipped Flutist was asked to play a song of remembrance, the national anthem, which gave praise to all the soldiers that died in the recent war. She was supposed to leave out the section that spoke of her brother, however, she refused and sang loudly about his valor. Many in the audience were awed by her bravery but many more left in disgust.

The Silencer, in response, by way of her family, ordered a apology to all of the people, or would force a vow of silence upon her. If she still grieved her brother, she would be silent to show it! Powerful shit!

What Rocked

Wow, this game was intense. The culture was educated and oppressive. The believed that they were better than all those around them, and that arrogance, and supreme belief in their nation was palpable in every interaction, as is intended by the game.

There are several parts of the the world creation that I adored. Specifically:

- Picking elements independently (and secretly) and then announcing them all at once and figuring out how to make sense of them. Ours were Silence, Ink, and Mountain. All which became powerful themes in our game.

- The traditions and the specifically the symbol of the tradition. It answered a really important question for me that I usually don’t answer in roleplaying games. Someone says “we always do X” and then you ask “How do we know that is true?” Or, what is the sign of that? The specific mechanics force you to create something that is emblematic which not only give concrete evidence, it also gives the players something specific to interact with. This is a brilliant mechanic!

- The themes of oppressive silence, of nationalism dividing people rather than biding people, and of people in dower arbitrarily drawing rigid lines was both daunting and poignant.

- This was a society that we could feel crumbling from the onset. The game did a wonderful job of constantly forcing us to incorporate the the flaw, so we never lost track of our trajectory.

What could have improved

Two hours wasn’t long enough for us. I think we could have sped things up a bit by using one of the Haven Guides, though I loved our society so much, I’m glad for this game that we didn’t.

The game is heavily reliant upon collaboration which I noticed initiated a lot of great discussions, but also took a long time. I think the elements that worked the best were when authority was passed to one person but they operated within a constraint (pick something from this list, draw a symbol, etc.)

A mountain top setting made us all very conscientious of cultural appropriation. We knew this wasn’t Nepal or Tibet or China or connected to Native American culture, but were concerned about adopting tropes and cliches from those cultures. For instance, we didn’t have a naming convention in mind, so we ended up giving the characters descriptive names. There are lots of cultures that do that, but we we’re really trying to avoid unintentionally aping one or the other. I wonder if others have run into this and what their reactions were. We just tried to stay aware of it and discuss the choices we were making with close scrutiny.