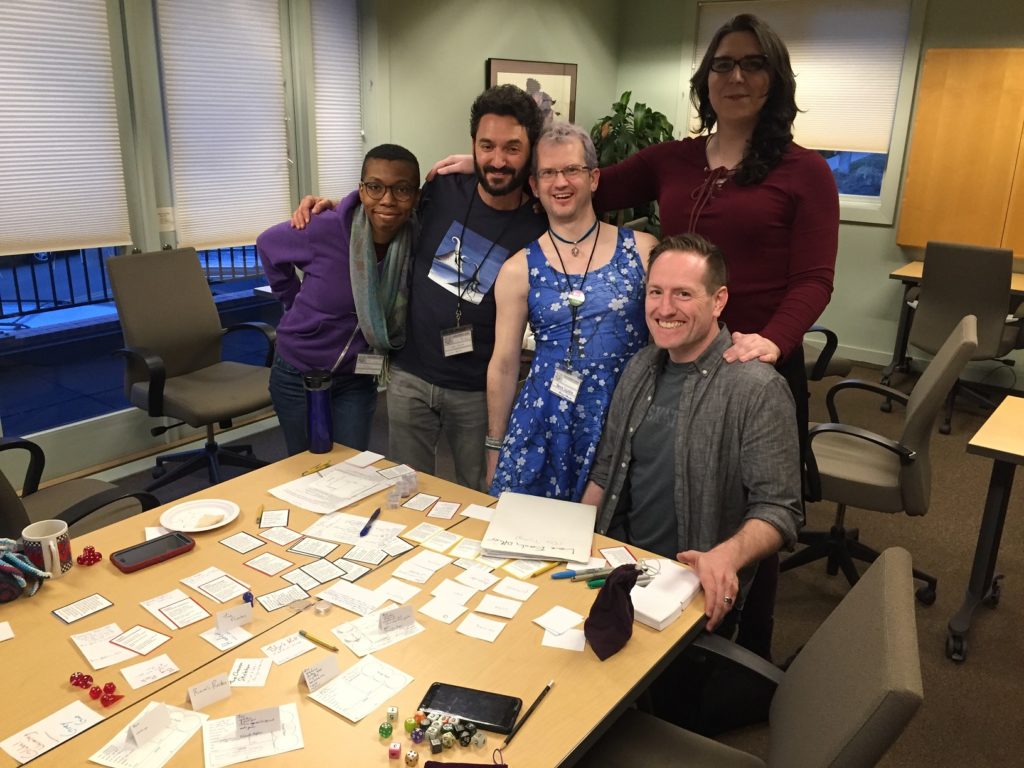

Facilitator: Venn Wylde

Players: April Walsh, Sean Nittner, Tomer Gurantz and Nadja Otikor

System: Love Each Other

We played a playtest game of Love Each Other, a procedural RPG that asks the question at the end, if a community can form in the spaces between concurrent apocalypses and in spite of still pervasive social norms.

Through the process of play we first identified the global sources of scarcity, the locations of our scenes and their aspects, the people in our world, the genders they identified with, and the scenes between them. In the end this culminated in a final determination to see if a society could be formed by giving each character a choice to sacrifice themselves, flee, or face the central aspect that defined them.

Love each other is built on a tech tree. From a visual and procedural perspective the game builds upon itself in a way reminiscent of minecraft. Small building blocks that add up to bigger things. One option unlocking others, with the ability to both broaden the world (by adding new people and places to it) and deepen it (by asking and answering questions about them, or by playing out scenes with them).

I had lots and lots of thoughts on this game, as a player (my personal tastes), as a playtester (mechanics I felt need work), and as a publisher (looking at it from the prospective of a retail product). So rather than my normal “here’s what happened” I’m going to do a breakdown of the game itself from those three perspectives and note the areas where they aren’t always in alignment. I’ll break them down into Roses and Thorns (areas that were rewarding for me and areas that didn’t work as well for me).

Player Perspective

This is just Sean as a player of games. It’s based on my personal preferences and are measured by the fun I had at the table and the emotional impact I felt playing the game.

Roses

I love development of tech in games. By giving a path for creating things, I become invested in their narrative significance. This game felt a lot like Roller Coaster Tycoon (one of the few games of that genre that I’ve played) in that you could make a world and then see how the things operated inside it. Each card played revealed the new tech under it, and when enough cards from one category were played, new categories opened up (for instance, once you have made two characters, you can have a scene between then).

The physical artifact of play was also rewarding. We could look at the table at any time and see what was going on, as well as what options were out there. I have other publishing thoughts on this below. As a payer I enjoyed the pageantry on the table.

As a cishet white man, I specifically appreciate the procedure that deconstructs queer narratives and teaches you how to tell them. This, in many way acted like training wheels for telling queer stories. Some of those themes (like enduring oppression and scarcity) I was familiar with and some of them (like defining gender) I hadn’t done before. Neverthless, like playing Dialect, I felt I had both created a thing, and learned from that creation.

Some of the meta/safety tools used in the game were familiar to me. There was a new one though that really liked. It’s like the “more of that” card in Archipelago, which is lightly tapping your fingers on the table to show you’re excited about what’s happening and you want to see more of it. I think it’s great to have that signal in game and I’m totally using that in games I facilitate in the future!

Thorns

The procedural aspects were tricky to keep track of. In part because each new process had it’s own procedure, and in part because there is only one of any given card (so therefore, only one or two people can easily read it at any given time). Since there are so many cards, I think it would be counterproductive to have multiple copies of them, still I found myself often having to ask what the procedure was again.

The turn based nature of the game was a little rough for me. Because the turns tended to be long (when I noticed this I timed two of them, which were 10 minutes and 8 minutes respectively) that means a lot of time where one person is talking and the rest of the table is listening. I was working hard to stay engaged and at some points I felt myself fading. Tea helped out as did having scenes with other players!

Potentially specific to this game (i.e. I’m not sure another session would have the same results) there were two elements of the game that I saw and understood but didn’t feel the impact of:

- The apocalypse (both present and coming) are described as world-wide threats however the global impact of them rarely came up. Instead we had localized interpretations of those which were the actual threats in our game. For instance our existing horror was global warming, which manifested as water levels rising and making very few areas inhabitable. It also meant for all sorts of toxic sea life as chemical spills went untreated and poisoned the creatures below. The oncoming apocalypse was grey goo that dissolved everything, and this one was much harder to link to directly. Early on introduced a black mold that had come up out of the water and the people who inhaled the spores were getting sick and dying. The allusion I was making was that their bodies did more that die, they dissolved and so we loosely connected those two threats, however it was a lot of heavy lifting on the players parts to link those things up.

- The scarcity presented with each location was worded in a very specific way that felt evocative, but not concrete. For instance Bly’s Hall was one the last places you could get warmth, the Chevron Skeleton was the last place to find food, and Hodge was the last place to find safety. We referred back to these scarcities frequently and did try to weave them into the scenes, but I never felt like our characters were struggling to find warmth, food, or safety. We’ll maybe safety, but I think in any game that is likely to be a scarcity. So we rarely talked about people getting sick, starving, being captured, etc, and I think those things would have impacted our characters had their been a visible mechanic enforcing their absence.

Playtester Perspective

This is angled specifically at what parts of play felt like they were running smoothly vs. areas where there was confusion or I felt challenged engaging.

Roses

Because the game is so procedural, whenever I ran into a question of “how does this work” or “what can I do next”, I could look at a card with directions. I don’t playtest games to try and break them, but I do like knowing that I’ve explored the options intended and the tech tree (as I’m calling it) was very helpful in that.

I’m not sure if this would be reproduced in the second playing of the game, but the feeling of “unlocking” new options and specifically getting to read them and start picturing how they might unfold was great. We had moments like “ooh, you can now have ‘Isolation’ as part of your game” which sounds macabre but in the game it made sense and helped us tell the story of these folks in this place.

Thorns

First, one I think will be easy to address. The create genders section of the game needed just one more example or step of guidance to help me along. Specifically, the instruction is for everyone to write some queer genders on index cards that we’d put in a pile, starting with “agender” which always goes in. Based on that example I was thinking of queer genders that I was familiar with and started with non-binary and was about to write trans woman. When Princess and Pooka were added to the pile, both defined at the table, and I realized that my gender contribution was a bit pedestrian and wasn’t sure if I should be stretching a bit further. For me the procedure would have benefited from a step that said to create and define new genders, to use existing queer genders, or to permission to do both.

Mid Scene resolution sounded like a good idea before we started the scenes but in the moment it felt jarring and I had trouble getting back into the scene after the discussion. Specifically during a scene (which always have something they are driving towards like intimacy, support, etc) as the scene progresses, at some point when the players feel like the characters may have made a connection we pause the scene to discussion who was seeking the scenes objective and if they made a connection. we assign love and fear dice accordingly and then act out the scene. The mechanical ramifications (love and fear) both worked really well for me, but the mid-scene break deflated all the emotional energy that had been building up during the scene. When we came back I was always stumbling to recapture it.

The gamer part of my brain found the “optimal” play style a bit too obvious. We should, as the name of the game indicates, love each other. So during scenes, I felt a tug between acting as I think a character might and acting as I thought I should be for the benefit of the table / game results, etc. More on this in the conclusion below.

Publisher Perspective

This is me thinking as a publisher that would want to put this on shelves, know how to market it, etc. I’m trying not to come specifically from a Evil Hat perspective, but I’m sure some of that is in there.

Roses

A very cool part of this game is that it can be played asynchronously. Because all of the creative contributions made (locations, characters, the results of scenes) are recorded on the table, a player can add more things to the game (answering questions about existing aspects, building out new locations and characters, etc) on their own. We didn’t actually do this during the game, but I could see how this would have a lot of appeal for long running games where players could made contributions between sessions. Also, I think it would suit play-by-post or play-by-forum games very well, as some players have more time to invest in the game and the could use that time to create more content.

There are some very smart choices in questions on the cards. Specifically choices that causes us to change our expectations. For instance when you define an antagonistic group, you’re reminded that they are still human and have to define a moment where they made a sacrifice to help you. Similarly when you create a group in need, you’re reminded that they also have their faults and are asked how they’ve hurt you. This breaks up a lot of stale caricatures that otherwise might be formed unintentionally.

I’m a big fan of the tableau of characters that are picked up and played as needed for the scene. Breaking down direct attachment between player and character can challenge investment (sometime we see the game through the avatar of our characters) but I think think the overall and longer term effect is to grow investment into the group as a whole and their predicament vs. investing heavily in your own character.

Thorns

As I mentioned in the player experience the length of turns was long by RPG standards, and because contribution from other players wasn’t always an option (especially before there were scenes), it might be 30 minutes between one player taking a turn or being actively involved. This was particularly noticeable because one of the players was never in a scene, so in four hours of game play, she didn’t get a chance to embody any of the characters we created.

While I personally enjoy the tech tree a lot, I also know that there are a lot of players who just want to “play the game” and would feel like everything building up to scenes was character and setting creation rather than play. The Quiet Year has a similar play format and I think Avery addressed those expectations by calling it a map making game rather than role playing game. Love each other might need an analogous description to prepare folks for the play of the game.

There was an ongoing uncertainty during the game of who “we” were. Love Each Other explicitly asks the question about whether or not we can form a queer community in a hostile world. So at the end of the game, we might be able to call ourselves a community, but during the game it was really hard to pin that down. Frequently we used the word “we” to describe people in the Big Pink or the Hodge (two of our locations), but those locations represented places where there had been communities that were no more. We also referred to “we” a the characters we had created on the table, but they weren’t a community yet. It’s a tricky thing to describe something in transition and I wanted some language to use to hold that idea in our minds so we (as players) were clear about who we were talking about.

Conclusion

I think Love Each Other exists in a liminal space between roleplaying and cultural anthropology. The procedure is comprehensive and allows us to create a simulation model and then watch now the pieces inside of it move. However, because accumulating love is a choice and it leads to a positive outcome, I feel like there is a tension between playing the game optimally and playing it to find out. The gamer inside us may strive to pick the best outcomes and “win” while the anthropologist will veer towards exploration and discovery. Like Dialect which bridges gaming and linguistics, I think Love Each Other has a long road to bridge to different fields.